Scenes are the building blocks of stories. Individual scenes should follow a specific arc that pushes your protagonist toward a pivotal choice moment that leads directly into the next scene. Collectively, each scene of your story should form a chain of reactions that tie plot events together while ramping up narrative drive.

Without solid scene structure, it’s really difficult to create a cohesive narrative, ensure your character’s arc of change is clear, and keep your reader’s attention.

But what actually makes up a scene? And how do you decide which scenes to include in your story and which to leave out? In this blog, we break down the building blocks of working scenes, with tips and tricks on how to fit your scenes to your story arc and ensure your readers stay engaged.

What IS a scene?

A scene is the smallest unit of a story that contains its own beginning, middle and end. The most defining aspect of a scene, however, is that it must mark a change in the story. In every scene, your character must face a problem that forces them to make a character-revealing decision that has story-altering consequences.

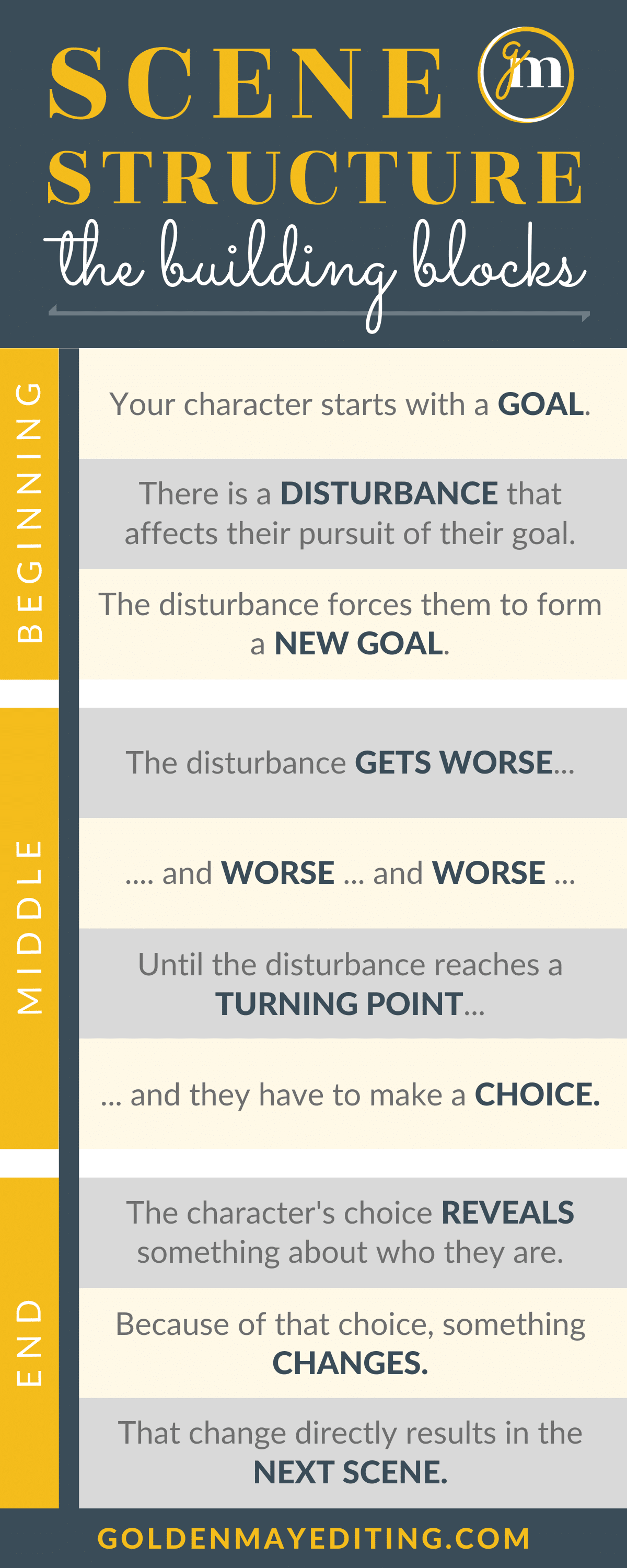

In this infographic, we summarize the key building blocks of scenes. But let’s break them down a bit further:

GOAL: All scenes should open with strong goals. Your character is trying to accomplish something, and it needs to be clear in the first few paragraphs. This goal should be a subset or objective of their larger story goal.

DISTURBANCE: This is your scene plot problem, or “inciting incident.” It can be a confrontation, a sudden conflict, an unexpected obstacle—anything that drags the protagonist away from their initial goal or makes their goal more difficult.

NEW GOAL: Your character can’t have the option to ignore whatever has happened (either they physically can’t ignore it, or their personality won’t let them), and so they’re launched into the pursuit of a new goal (whether it’s an altered version of their original goal, or an entirely new one, this new plan should still be tied to their overall story goals).

GETS WORSE: As your character pursues their new goal, the original disturbance (whether good or bad), complicates repeatedly—spiraling your character toward the scene’s turning point. NOTE: These don’t have to be negative beats, they just have to complicate the character’s pursuit of their original goal. They can even be positive, pushing them toward success in unexpected ways.

TURNING POINT: Your disturbance has gotten so intense that your character can’t ignore it anymore. The turning point is when they come face to face with a decision and they have to act. Whether they have two options or ten, every option needs real consequences.

CHOICE: The turning point must force your character to make a decision—and it needs to be hard. Make sure every option they face has risks. They must stand to lose something regardless of how they act.

REVEAL: Because the dilemma your character faces will have consequences no matter what they do, their ultimate choice will prove something about who they are and what they value. As the story progresses, and the consequences of their decisions get worse, your character will be forced to change. As a result, the choices they make at the end of the story will drastically differ from those they made at the beginning.

CHANGE: Since the choice your character made had consequences, something will change immediately, either inside them, in their relationships, or in the external plot.

NEXT SCENE: To keep your reader engaged, your scenes must be tied together in a cause and effect trajectory. At the end of each scene, ask yourself: “Because of what happened in this scene, what will my main character inevitably do next?” OR “What is the inevitable plot result of my character’s choice?”

Common questions

Does a shift in setting mean a new scene has to start?

No! A shift in setting often indicates a shift in scenes, but it doesn’t have to. As long as all the beats of scene structure are present, and the scene’s goals are driving to a clear and connected choice moment, then you can hop multiple settings!

Are chapters and scenes the same thing?

Chapters and scenes can be the same, but often they’re different! Many times a chapter will consist of multiple scenes. You’ll often see a scene chopped at a Turning Point beat as a cliffhanger for one chapter, with the Choice and subsequent beats unfolding in the next.

Won’t putting all of these beats in every scene make my story too long?

Your scenes need these beats in order to feel complete. If your character lacks clear goals, the scene won’t feel like it’s moving the story forward. If there isn’t a disturbance, the scene will lack intrigue and conflict. If your character doesn’t have to make a choice, the scene will lack drive and agency. The other beats are critical to tying goals → choice in a cohesive and clear way. If you think using this structure will make your scenes too long, aim to cut scenes rather than scene beats. Chances are, you have more scenes planned than is necessary to tell your story in a tight, cohesive way.

Do the GOAL and NEW GOAL beats have to be related?

Your character should open each scene with a very clear goal that gets interrupted by an unexpected disturbance that leads them to develop a new goal. These goals can be connected (ie. the character has to figure out a new way to achieve their original goal) OR they can be totally disconnected (ie. the character has to drop their original goal to deal with this new problem). Overall, however, BOTH goals should be somehow connected to your character’s overall story goals and plans so the scene remains relevant!

How does one scene fit within a larger story?

By now you understand that scenes revolve around decisions and change. If every scene ends with a choice that leads to consequences that lead to the next scene, then every scene will be connected by a string of choices that lead to the story’s inevitable climax.

Every scene choice should link, in some way, to your character’s arc by challenging your character’s Internal Obstacle (the belief, worldview, or fear they have to overcome in the story). If a scene’s decision point doesn’t advance toward your story’s ultimate climax, then you should find a way to connect it, or consider cutting it altogether.

I know this can be hard to wrap your head around, so let’s look at an example:

A Scene within an Arc: A Game of Thrones

THE SCENE: In one of the first scenes of A Game of Thrones, we see Jon Snow at a welcome feast for visiting royals. Because of his status as a bastard, Jon is forced to sit with the commoners, rather than his family—and he’s grumpy about it. In the scene, Jon asks his Uncle to bring him to join the Night’s Watch, where he thinks he can find glory and escape the dishonor of his bastard name. At the end, he loses his temper and nearly cries in front of the commoners. He ends up abandoning the argument and fleeing the hall, determined to save face and honor.

THE CHARACTER ARC: Jon Snow’s overall story arc in A Game of Thrones is about honor and glory. At the climax of the book, Jon will be forced to choose between running off to avenge his father’s death alongside his brother, or staying with the Night’s Watch (which he’s pledged his life to) to protect the Wall from the rising dead beyond it. His Commander puts the question bluntly, and beautifully, “Are you a brother of the Night’s Watch . . . or only a bastard boy who wants to play at war?”

HOW THEY FIT TOGETHER: While a royal feast scene in the first act might seem random, and perhaps irrelevant, George R. R. Martin fills every page—from descriptions to decisions—with symbolism about honor and glory. We see Jon equating one for the other, and making a scene choice about how to preserve his pride (which, at this point, he mistakes as honor). With these tactics, Martin places the scene snuggly in Jon’s arc toward his ultimate choice between glory and honor.

Unlocking scene structure is the key to understanding story structure. See if you can identify these building blocks in scenes from stories you love! The better you get at identifying them, the easier it will be to write using them.

thannks for the insight!

That was fascinating! Thanks so much for posting C: I especially loved your emphasis on the decision being character-revealing. I wrote an article on Scene Structure myself several months ago, but I forgot to mention how important that this ~

Thanks Halley! So glad you found it useful. Yes, that scene decision point is so important and so easy to overlook! We’ll be posting something soon about how to tie scene decisions to character arcs, so keep an eye out, you might find it interesting! 🙂