Scenes are the building blocks of stories. A scene has its own beginning, middle and end. The best scenes contain plot problems that push your protagonist to make a character-revealing decision that changes them or their world.

To ensure your story is driving forward, with your character at the helm, they must enter each scene with a goal that a problem gets in the way of, forcing them to make a choice that has consequences for future scenes. Without this structural chain of reactions, it doesn’t matter how well written your prose, dialogue, or descriptions—your scene will risk falling flat.

But what actually makes up a scene? And how do you decide which scenes to include in your story and which to leave out?

In this blog, we break down the building blocks of working scenes, with tips and tricks on how to fit your scenes to your story arc and ensure your readers stay engaged.

What IS a scene?

A scene is the smallest unit of a story that contains its own beginning, middle and end. The most defining aspect of a scene, however, is that it must mark a change in the story. In every scene, your character must face a problem that forces them to make a character-revealing decision that has story-altering consequences.

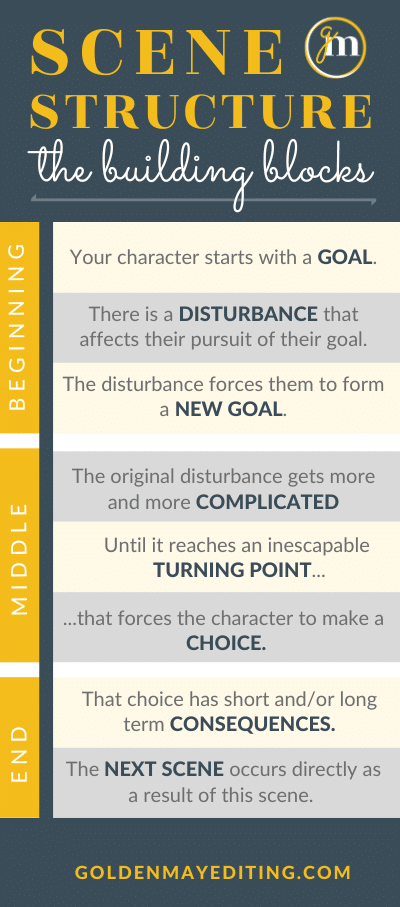

In this infographic, we summarize the key building blocks of scenes. But let’s break them down a bit further:

GOAL: Begin your scene with your character setting out to accomplish something (even if that something is nothing!). Make it clear in the first few paragraphs what they want, and how they intend to get it. This goal should be a subset or objective of their larger story goal.

DISTURBANCE: This unexpected problem can be a confrontation, a sudden conflict, or an obstacle—anything that prevents the protagonist from continuing their original plan to achieve their Goal.

NEW GOAL: Your character doesn’t have the option to ignore whatever has happened (they physically can’t, or their personality won’t let them), and so they have to come up with a New Goal and plan for achieving it.

COMPLICATIONS: The Disturbance gets progressively worse, spiraling awry and out of control.

TURNING POINT: The Disturbance and its ripple effects finally corner your character into a moment in which they MUST take action. This Turning Point must be specific (a single line of dialogue, an action, a revelation).

CHOICE: The inescapable Turning Point corners your character (not a side character) into making a really difficult choice that has stakes for all options. Whatever they choose reveals something about what they believe about how they must act to get what they want.

CONSEQUENCES: Every choice a person makes has consequences, both immediate and longer term. The consequences of your character’s choices should have ripple effects on the future plot events and their relationships with other characters in the story.

NEXT SCENE: In order to keep your reader engaged, and your story’s tension and pacing pushing forward with good narrative drive, you need each scene to tie into the next. Use the consequences of the character’s scene Choice to set up their Goal and/or the plot circumstances in the next scene.

Common questions

Does a shift in setting mean a new scene has to start?

No! A shift in setting often indicates a shift in scenes, but it doesn’t have to. As long as all the beats of scene structure are present, and the scene’s goals are driving to a clear and connected choice moment, then you can hop multiple settings!

Are chapters and scenes the same thing?

Chapters and scenes can be the same, but often they’re different! Many times a chapter will consist of multiple scenes. You’ll often see a scene chopped at a Turning Point beat as a cliffhanger for one chapter, with the Choice and subsequent beats unfolding in the next.

Won’t putting all of these beats in every scene make my story too long?

Your scenes need these beats in order to feel complete. If your character lacks clear goals, the scene won’t feel like it’s moving the story forward. If there isn’t a disturbance, the scene will lack intrigue and conflict. If your character doesn’t have to make a choice, the scene will lack drive and agency. The other beats are critical to tying goals → choice in a cohesive and clear way. If you think using this structure will make your scenes too long, aim to cut scenes rather than scene beats. Chances are, you have more scenes planned than is necessary to tell your story in a tight, cohesive way.

Do the GOAL and NEW GOAL beats have to be related?

Your character should open each scene with a very clear goal that gets interrupted by an unexpected disturbance that leads them to develop a new goal. These goals can be connected (ie. the character has to figure out a new way to achieve their original goal) OR they can be totally disconnected (ie. the character has to drop their original goal to deal with this new problem). Overall, however, BOTH goals should be somehow connected to your character’s overall story goals and plans so the scene remains relevant!

7 key attributes that make good scenes great

✨ The scene ties to your story’s POINT.

Every story reveals something about what the author believes (ie. If a person does/believes X, then Y will happen). In your story, each scene should in some way touch on this point. This often happens in the choice moment of the scene, when what the character believes influences their decision making.

✨ Your main character has AGENCY.

The hearts of readers aren’t won by passive characters that just allow things to happen to them. Make sure your protagonist has a clear Goal in every scene and is taking action in pursuit of that goal. Your character must take the initiative to do something about their circumstances, even if their choice has negative or unforeseen consequences.

✨ The scene’s CONTEXT is clear.

Ground the reader in the story at the very beginning of each scene, especially in relation to the scene before it. New location? Make that obvious. Has time elapsed? Let us know exactly how long.

✨ SHOW, don’t tell.

Make sure to always show how a scene’s spiraling events are affecting your character. What are they thinking as things go awry? What does it feel like in their bodies? We want to live their experience!

✨ DESCRIPTIONS are story relevant and serve multiple purposes.

Instead of describing something or someone just for the sake of visuals, use descriptions to reveal how your character is feeling, who they are and what they want, or to foreshadow information the reader will need to make sense of the story later. By showing us how the character processes their world, you will inevitably keep your descriptions brief and meaningful. You’ll engage, rather than bore or confuse, your readers.

✨ The character understands the world through BACKSTORY.

As humans, we use past experiences to make sense of the present. The best way to get your reader in your character’s head is to use backstory to show how they understand what’s happening around them in the story present and how they feel about it.

✨ DIALOGUE is relevant to the scene.

Dialogue should only be used in service of a scene’s beats: establishing context or Goals, causing or complicating Disturbances, or revealing character Choices / Consequences. If your dialogue doesn’t do one of these things, you probably don’t need it!

Unlocking scene structure is the key to understanding story structure. See if you can identify these building blocks in scenes from stories you love! The better you get at identifying them, the easier it will be to write using them.

thannks for the insight!

That was fascinating! Thanks so much for posting C: I especially loved your emphasis on the decision being character-revealing. I wrote an article on Scene Structure myself several months ago, but I forgot to mention how important that this ~

Thanks Halley! So glad you found it useful. Yes, that scene decision point is so important and so easy to overlook! We’ll be posting something soon about how to tie scene decisions to character arcs, so keep an eye out, you might find it interesting! 🙂